We may be inclined to think that anything written 700 years ago will be very far removed from our lives today, and that we would struggle to relate to the material and themes that any writer from that period would choose to tackle.

Katie Bastiman, who studied Dante at the University of Oxford and now teaches evening classes on The Divine Comedy through the Adult & Community Education programme of Highlands College, explains why, for most people who engage with Dante’s ‘The Divine Comedy’, this is not the case.

The 25th March is Dantedì – or Dante Day – 2023, which is an Italian National day for the celebration of Dante’s life and literary works. However, Dante is read and loved beyond Italy, including here in Jersey, where there is a growing community of learners engaging with his text.

To mark Dantedì, I want to take the opportunity to reflect on what this poem is about, why it was so important at the time in which it was written, and why we can still relate to it today.

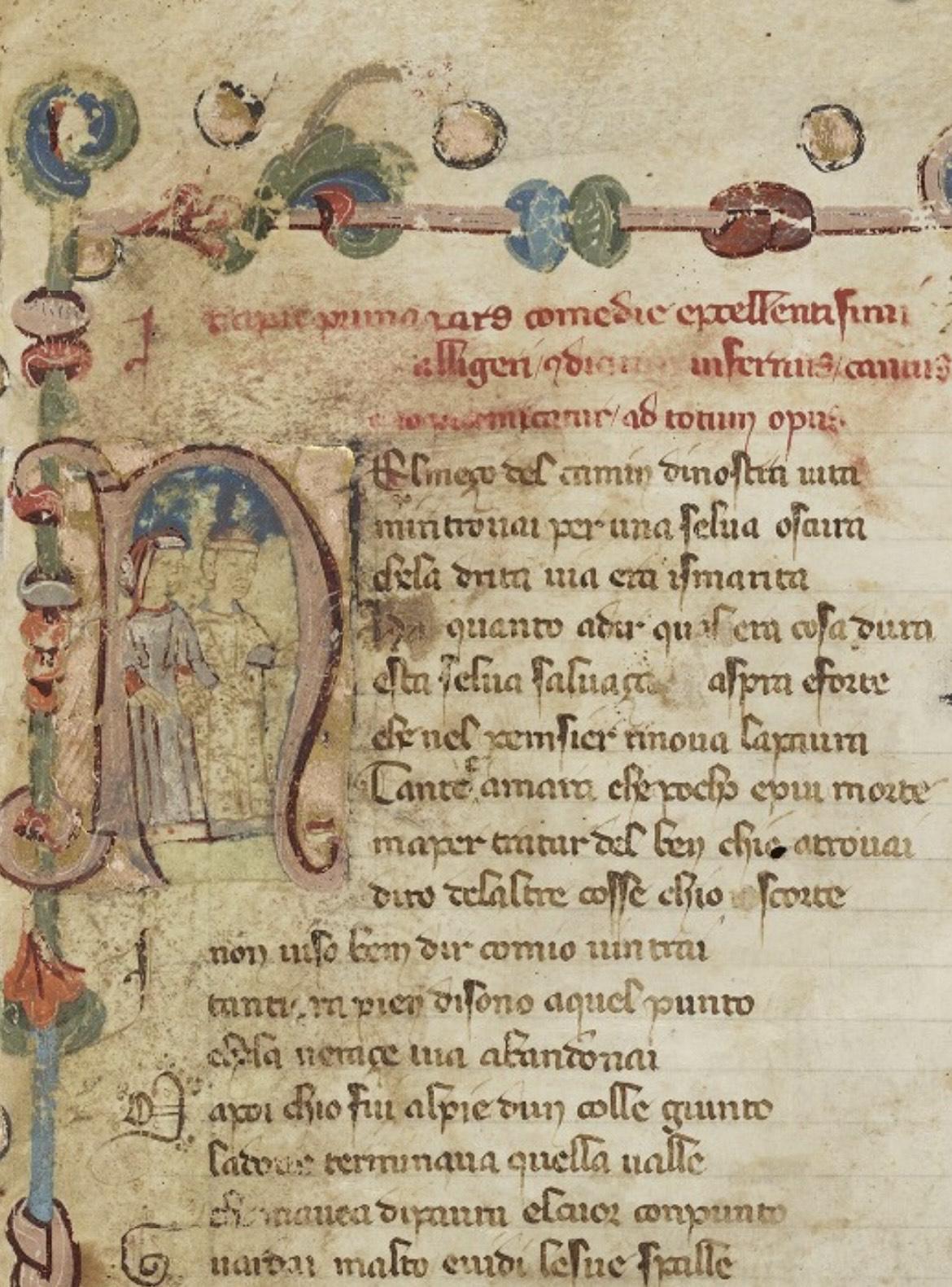

‘The Divine Comedy’ is a medieval Italian poem which was written roughly between 1302-1321 by the poet Dante Alighieri. It tells the story of a journey through the three realms of the afterlife – Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Dante wrote a variety of works but the Comedy (‘La Divina Commedia’ in Italian) is the most famous.

This great poem was hugely influential on Italian culture and society and its impact can still be felt today. Dante writes himself into the story as the main character, who must travel through the afterlife and speak to the souls of the dead in each of the three realms. He is guided by the classical poet, Virgil, whom he greatly admired.

That may not sound particularly relatable, but ultimately the Comedy is an examination of what it is to be human. Morality, desire, fear, knowledge, friendship, self-improvement – these are all key topics addressed by Dante’s text. It is not only interesting as a reader to see how those themes were thought of in the 1300s, but, arguably, to see how little has changed in terms of human psychology since that time.

And whilst there are moments of humour in the text, that is not why it’s called a comedy. Here, we are using the opposite model from a tragedy, in which you begin in a good situation and end up in a bad one. In Dante’s text, the protagonist begins in a bad situation – lost in a dark wood – and ends up in a good one – reaching salvation.

The first part of the Comedy, Inferno, details Dante’s journey through the nine circles of Hell. The poet creates a structure for Hell by dividing it into layers (or circles), with a different sin being punished in each one. Every circle is home to a range of historical, biblical, and mythological figures, as well as ‘celebrities’ from Dante’s contemporary society – I imagine that he may have had some fun deciding which areas of Hell were most appropriate for his enemies.

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here” may be a familiar phrase, and it originates from Inferno, where it is written above the gates of Hell. As the main character (sometimes referred to in scholarship as ‘the pilgrim’) travels deeper into Hell, he interacts with the souls residing there. These range from tragic lovers condemned for their lust, and gluttonous souls who now writhe in muck like pigs, to those guilty of more serious crimes. Souls who were violent in life are now condemned to boil in a river of blood; those who fraudulently betrayed family or friends are doomed to be frozen up to their heads in ice for all eternity as punishment for their cold-heartedness.

Inferno is, perhaps, the goriest section of the poem – which for many people makes it the most fun to read. But besides the horrifying tortures dreamed up by Dante, there is much more to be found here. The relationship between Dante and his guide Virgil is, to me, one of the more touching elements of the poem.

Even within the darkness and claustrophobia of Hell, a deep friendship is formed. Dante sees Virgil as his poetic forefather, an inspiration and a mentor. In moments of fear, he leans on his companion – sometimes literally – until he gathers the strength to continue. We should all hope to have such an ally on our journey through life.

And, in contrast to the hopelessness of the souls stuck in Hell forever, Dante and Virgil’s journey through this space is motivated by hope. Hope that they will make it through this wretched space and come out the other side, and that they will learn valuable lessons from this experience. And make it out the other side, they do – quite literally.

Dante envisaged Hell as a funnel, leading down towards the centre of the earth, where Lucifer is trapped in a frozen wasteland. To escape Hell, the pair must go all the way through, passing Lucifer, then following a path until they make it out on the other side of the globe. That journey makes up the first third of the Comedy and leads us to the shores of Purgatory. The idea that we must sometimes journey through hell in order to come out on

the other side and reach safer waters certainly still resonates with readers today.

Next up, is Purgatorio, which Dante depicts as an enormous mountain. In some ways, Purgatory is the opposite of Hell – rather than moving downward in concentric circles, with the worst sinners at the deepest point, on the mountain of Purgatory we move upwards, burning off the worst sins first until eventually, the souls have been purified and can ascend to Heaven. For Dante, the difference between whether a soul went to Hell or to Purgatory was not whether or not they had committed any sins in life, it was whether they prayed for forgiveness and repented before they died.

A soul that repented and made it to Purgatory has the chance to ‘work off’ their sins over time, unlearning their worst flaws until they have been purified.

Purgatory is in many ways the most human section of the poem, because it is a space where change is possible. Souls damned to Hell or blessed in Heaven will remain in the same state for eternity, but those in Purgatory are still working on improving themselves until they are worthy of going to Heaven. This self-improvement takes time, effort, and desire to change – all key ingredients that readers of the Comedy may recognise from any attempts they have made to implement positive changes in their own lives.

Dante and Virgil travel together up the mountain, and again they speak to a range of souls at different points in their journey, learning about the stories and personal dramas of fictional and mythological characters and real people from Dante’s day. At the top of the mountain is the Garden of Eden, the final point that a soul must pass through before they can ascend to Paradise and reunite with God. Dante bathes in the river there and becomes pure and ready to journey through Heaven.

The third and final part of the poem, Paradiso, is probably the most complex, but is also widely regarded as the most beautiful. Dante conjures images of dancing lights, heavenly singing, and total harmony between all beings, whilst also examining a number of theological questions. The souls he speaks to here exist in a state of perfect happiness, yet they still have stories to share and wisdom to impart. Dante moves through the different spaces of Heaven, which he mostly represents using the planets, until he ultimately reaches a vision of God.

Dante lived between 1265 and 1321, so 2021 was the 700th anniversary of his death. Nevertheless, his literary genius has secured him a lasting legacy which will surely live on for many years to come.

If we can still pick up his poem over 700 years after it was written and find our own experiences, desires, fears, and concerns reflected in the words on the page, then I think that legacy is well-deserved.

Katie studied Dante at the University of Oxford and now teaches evening classes on The Divine Comedy through the Adult & Community Education programme of Highlands College. Her next course will begin on Thursday 18th May and will run for 6 weeks. Click here for more information about Katie’s evening classes or to sign up for her next introductory course, “Dante Book Club”. Please contact Katie to find out more.