Join Giles Robson for this week’s Deep Listening column. Today we focus on Little Walter’s ‘Juke’.

In the case of most rock and popular music writing, to quantify a genius when it comes to instrumental virtuosity and innovation is to label the artist the ‘Jimi Hendrix’ of their instrument. It’s used so often that it’s become a cliché, the sharpness of the meaning has been blunted through overuse. But a Jimi Hendrix comparison is perhaps no better used to describe this week’s subject of deep listening, blues harmonica legend Little Walter Jacobs. It couldn’t be a more perfect fit.

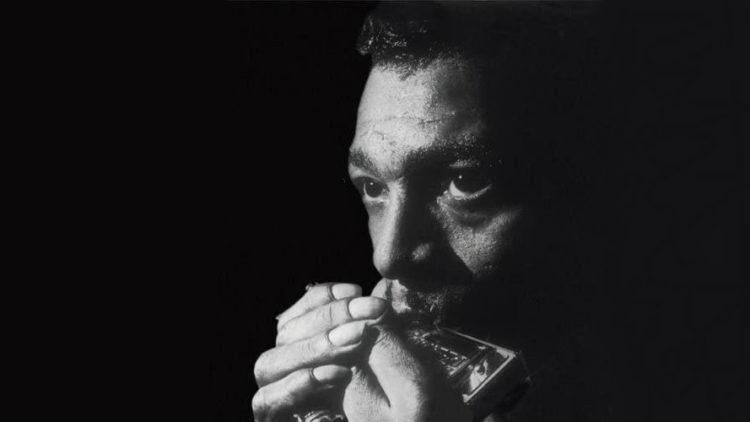

© Brian McMillen

www.brianmcmillenphotography.com

Almost instantly, Little Walter, like Hendrix with his debut album ‘Are You Experienced’, redefined his instrument – the harmonica – not only through revolutionary playing technique but through the use of amplification and distortion. Like Hendrix, he arrived fully formed and his first piece of work created a ‘before and after’ line in the history of music for his instrument and achieved instant popular success with the public.

A younger harmonica player, James Cotton, who witnessed the impact of Little Walter’s success testified to the fact that the arrival of Little Walter was like the arrival of The Beatles in terms of Impact. Jazz giant Miles Davis described him as “One of the greatest creative geniuses of his time” and fellow Jazz titan Count Basie used to take his musicians to his live shows to hear how he constructed solos.

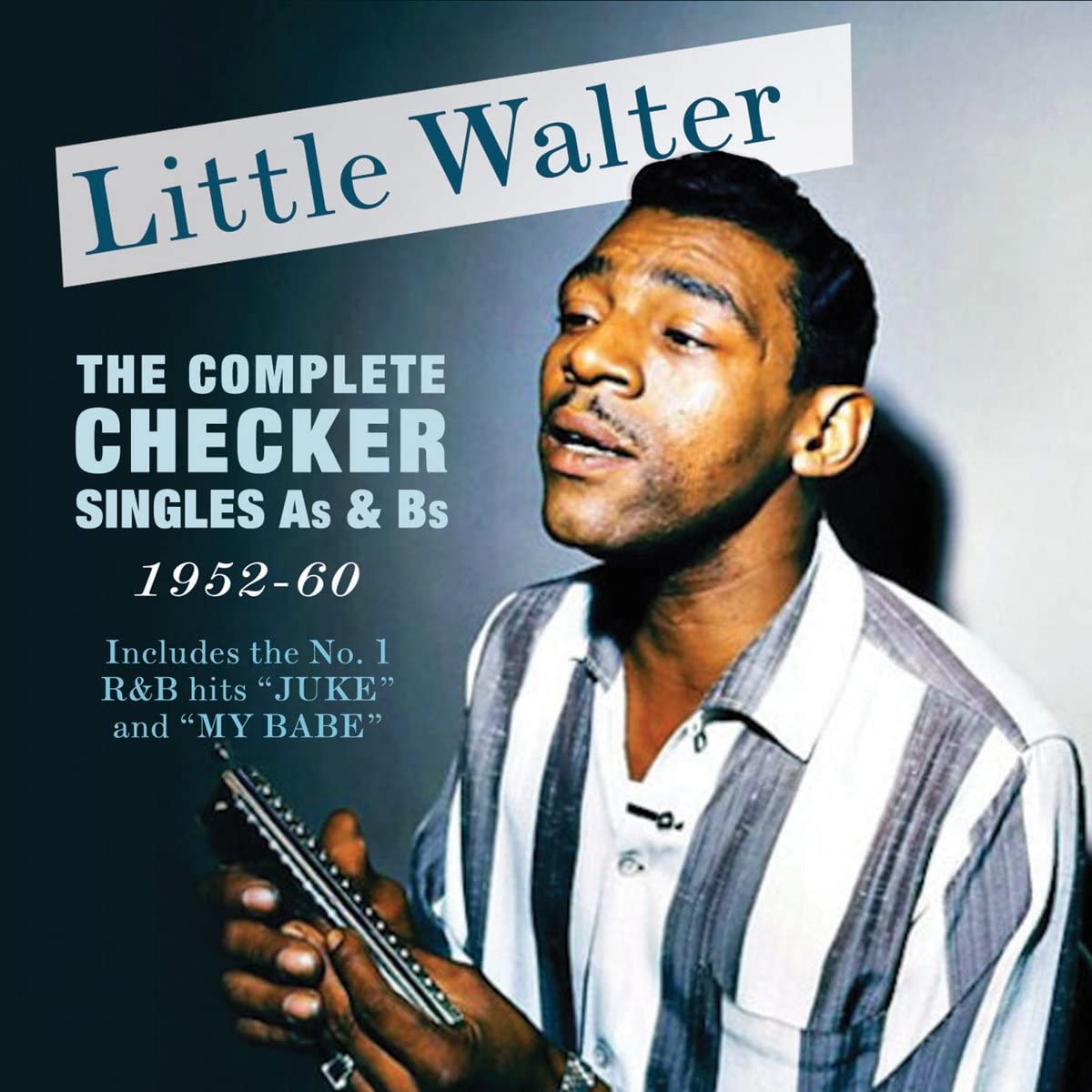

It was the release of his first single under his own name in July 1952 on Chicago’s Chess record label that arrived, seemingly out of nowhere, and instantly redefined the blues harmonica in terms of everything about the instrument that had come before – emotional range, technique, composition, and the ground-breaking creative use of amplification.

Walter’s first single was an instrumental track called Juke and upon its release reached the number one spot on the Billboard RnB chart for a staggering 8 weeks and stayed on the chart for a total of twenty weeks becoming the biggest hit of the Chess record label to date and one of the biggest RnB hits in the USA of the whole of 1952 and the only harmonica instrumental to hit the number one spot.

Superficially, what Walter had created with Juke was the blues harmonica equivalent of a tenor or alto saxophone led RnB instrumental. In the late forties and early fifties, sax led RnB was fashionable, exciting and profitable and Walter had been listening to and copying RnB saxophone ideas on the harmonica.

In striving to match their inherent technical precision and phrasing ideas he fully defined every available note of the diatonic harmonica with startling new clean execution that superseded his harmonica playing predecessors in Chicago John Lee, ‘Sonny Boy’ Williamson: and Snooky Pryor.

The great blues writer Robert Palmer defined RnB as “Urbane, rocking, jazz based music with a heavy, insistent beat”. RnB instrumentals were streamlined and simplified commercial form of instrumental jazz, with catchy straight forward horn riffs or melodies designed to cut through at loud taverns, roadhouses and bars for dancing and romancing. Music for the everyday folk, without artistic pretensions but nonetheless often designed with a lot of artistry.

Examples of sax RNB instrumentals can be found across the 1952 RnB charts – Jimmy Forrest’s ‘Night Train’ , Earl Bostic’s ‘Flamingo’ and Illinois Jacquet’s ‘Port Of Rico’: and also you can hear the sax led approach incorporated into vocal tracks such as ‘Mary Jo’ by the Four blazes (which features a sax led ending surprisingly similar to Walter’s ending of Juke).

Walter’s Juke fitted right into this landscape – but surprisingly offered something more. When listening back to the blaring sax men – the startling major difference between their approach to playing and Walter’s approach to playing on Juke, is the tonal sensitivity and dynamics on what is on the surface, a dance tune to party to. Through his playing Walter imparts a higher degree of significance through his sound than the all-out ‘raunch’ of an Earl Bostic or Jimmy Forrest.

Walter’s sound is at once sensitive, elegant, graceful, playful and dignified and he almost has the bearing of a classical musician.

The musical ideas are well thought out and flow entirely logically from one verse to the next, building and releasing tension and telling a story throughout the whole track. His restraint also creates a wonderful simmering tension between himself and the band, in that he refuses to go all dynamically out, but holds back just enough to keep you on the edge of your seat and holding your attention.

This higher degree of technique and concept on the blues harmonica wasn’t entirely unprecedented by 1952, and neither was the idea of garnering ideas from the saxophone. An older, and slightly shady master of the harmonica who would also highly successfully record for Chess Records in the forthcoming years, Rice Miler, had dubiously started to record under the name of Sonny Boy Williamson (the original Sonny Boy, John Lee Sonny Boy Williamson had been murdered in 1948 at the age of 34) had a series of releases the year before the release of Juke, in 1951, on the small Trumpet Records label from Jackson Mississippi. His biggest hit from 1951 on Trumpet was ‘Mighty Long Time’.

These sides showed a similar precise technical mastery of the instrument and lines that were in part based on driving saxophone parts. Miller’s harmonica work was purely acoustic, beautifully expressive, technically impressive and rich with emotion and played with an amazing sense of rhythm and timing. Walter had spent time with Rice Miller in the not too distant past and there are elements of Rice Miller’s playing that Little Walter quite clearly used.

However, Walter’s playing went further than Rice Miller’s in terms of melodic ideas and melodic range, composition and the now legendary use of amplification. Walter played through a cheap bullet shaped intercom mic – the size and shape of which was perfect to cup a harmonica against in your hands. The mic was then plugged into a valve-guitar amp creating a deeper more sonorous sound than the harmonica played acoustically.

However, Walter’s playing went further than Rice Miller’s in terms of melodic ideas and melodic range, composition and the now legendary use of amplification. Walter played through a cheap bullet shaped intercom mic – the size and shape of which was perfect to cup a harmonica against in your hands. The mic was then plugged into a valve-guitar amp creating a deeper more sonorous sound than the harmonica played acoustically.

The resultant distortion, created by the mic and amplifier combination, gave an uncanny resemblance to slightly raspy edge of the tenor sax sound.

It gave him a sonic playground to explore, creating a brand-new sound to announce his arrival on the scene. The amplification gave his harmonica a rich urbane edge – and made it seem a million miles from its rural sounding acoustic version.

But technique and amplification aside – Walter’s impact, much like Jazz Manouche guitar genius Django Reinhardt, was down to the rich emotion and sensitivity of his playing and his own personalised artistic concept. From Juke onwards, his catalogue of massively successful hits and inspired pieces recorded under his own name and as a sideman to Muddy Waters and Jimmy Rogers hammer home the ultimate truth that the power of music is the partnering of unique creative and emotional viewpoint with superb technique and technical advancements like amplification. That superb technique and technical advancements in terms of equipment are nothing without artistic and emotional weight.

I’ve made comparisons with both Hendrix and Reinhardt but ultimately it’s Miles Davis, who I really believe he is closest to. Walter’s music contained a fragility of emotion and a certain stark, poised melancholy at times that is reminiscent of Miles Davis. This artistic and emotional richness is why he stood out in the commercial landscape of the early to mid-fifties, and is also perhaps why, even to this day nearly seventy years later, it is felt that his revolutionary playing is unmatched.