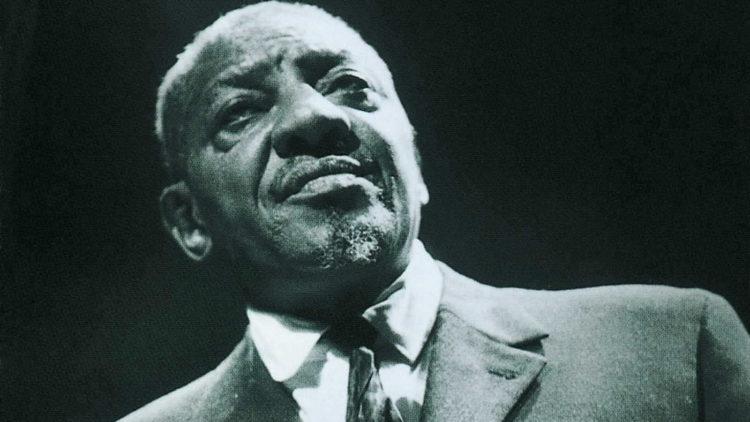

Only two pieces of music have caused me to shiver in involuntary delight and both are by the same extraordinary African American blues musician, Sonny Boy Williamson.

He died in 1965 some 13 years before I was born but his reputation has only grown over years and he is widely considered one of the classic giants of blues music as a singer, harmonica player, songwriter and performer. Both pieces were recorded just about a month apart in the autumn of 1963 and both, surprisingly were not recorded in the then blues music hotspots of the USA, but rather this side of the Atlantic in Manchester and Copenhagen.

African American music has been the foundational cornerstone of popular music for well over 100 years. From the Dixieland jazz bands of New Orleans in the early part of the 20thcentury to the Hip Hop artists and groups of today, a familiar pattern emerges. A music style gains popularity in the African American communities, then gets discovered and consumed by audiences around the world who inevitably start creating their own versions of it.

A striking contemporary example of this process can be found in Iran. Unlikely as it may seem, Iran has a thriving and fertile Hip Hop scene. It is known as “Persian Hip Hop”. This video from last last year presents the top 5 Iranian Hip hop artists here.

It’s perhaps as hard to imagine the early African American creators of Hip Hop predicting the reach and impact of the music to places as far away as Iran as it’s as hard to imagine the African American creators of blues music predicting a whole generation of teenagers across Europe and the UK in the 1960s falling in love with and then performing and recording their music – which to that point had been confined to the African American rowdy ghetto taverns and clubs of the major North American cities like Chicago.

However, in the early 1960s, that’s exactly what happened. After a couple of decades of sophisticated jazz being the popular African American musical import, it was the turn of the working-class blues, (just as it was going out of fashion with its own African American audience), to infiltrate the imagination of worldwide audiences, especially in the UK and Europe.

In 1962 two German promoters, Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau, sensed a commercial opportunity to present a yearly blues package tour that would run for the next nine years and then have a renaissance in the eighties.

They brought over a collection of some of the finest African American blues musicians on the USA scene. Legendary names over the years included T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, Howlin Wolf, Junior Wells, Son House and Skip James. They started selling out massive prestigious concert halls across Europe of 1800-2500 people and featured on expensively produced television specials going out to audiences of tens of thousands and produced a record of the live performances each year, also selling in the tens of thousands.

All the artists got a rapturous reception, but in the 1963 tour one artist stood out above the rest, for the critics and the audiences alike. The undisputed star of the show was Sonny Boy Williamson and when we listen to the recordings and watch the videos of his performances on the American Folk blues festival shows, we can understand why.

In the USA these now famous blues artists were used to playing to loud audiences who were half listening to the music and half socialising and drinking. The records that these artists recorded were raucous and loud to match atmosphere in the clubs where they would be played – the equivalent of what we would consider a pub over here. In terms of Jersey, think of a full Chambers in 2007 on a Saturday night!

In Europe and the UK, these blues performers were plunged into playing in concert halls designed for hosting operas and classical music concerts with perfectly designed acoustics and silent and sophisticated European audiences. These audiences would sit stony faced, dressed up for an up -market concert experience sitting silently and focusing on the stage and concentrating on every single note sung and played by each artist – like they would an opera singer, orchestra or string quartet.

When we look at the video footage today, some of these classic blues artists noticeably struggle to relax and work the highly formalised situation and with much less volume but far more detail than a bar gig would require. Not Sonny Boy, Sonny Boy flourished in these conditions.

He captivated these huge, sophisticated and deadly quiet audiences by holding back when playing and singing. When he performed it wasn’t a just thoughtless surge of incredible musical talent. The spine-chilling musical magic came from the knife edge tension he created by restraining himself and trying to play as few notes as possible but infusing each note with as much musical thought and sensitivity (rhythmical, textural, dynamic, tonal and emotional) as he could.

He phrased and designed his solos and singing with his own sense of incredible musical logic that left a lot of space between notes and thus he created a sense hunger as to what note would come next. His sense of design was wedded exclusively to the twelve-bar blues and to successfully exploit the potential opportunities of its fixed structure to the max. Of course, all of this was perfect for a large acoustically perfect concert hall where a sea of eyes and minds were focused entirely on the performer under a professional lighting system.

He seemed, when performing, to be as much trying to fascinate himself as fascinate the audience and all the while hiding this complexity behind a couldn’t care less attitude – a classic ironical double bluff that the audience was subtly informed of by the not unaware glint in his eye. His approach was described by no less than The Sunday Times as “Perfect artistry” and by a European newspaper reviewer from Strasbourg described him as “Homo Ludens (the spirit of play) in human form”.

He seemed, when performing, to be as much trying to fascinate himself as fascinate the audience and all the while hiding this complexity behind a couldn’t care less attitude – a classic ironical double bluff that the audience was subtly informed of by the not unaware glint in his eye. His approach was described by no less than The Sunday Times as “Perfect artistry” and by a European newspaper reviewer from Strasbourg described him as “Homo Ludens (the spirit of play) in human form”.

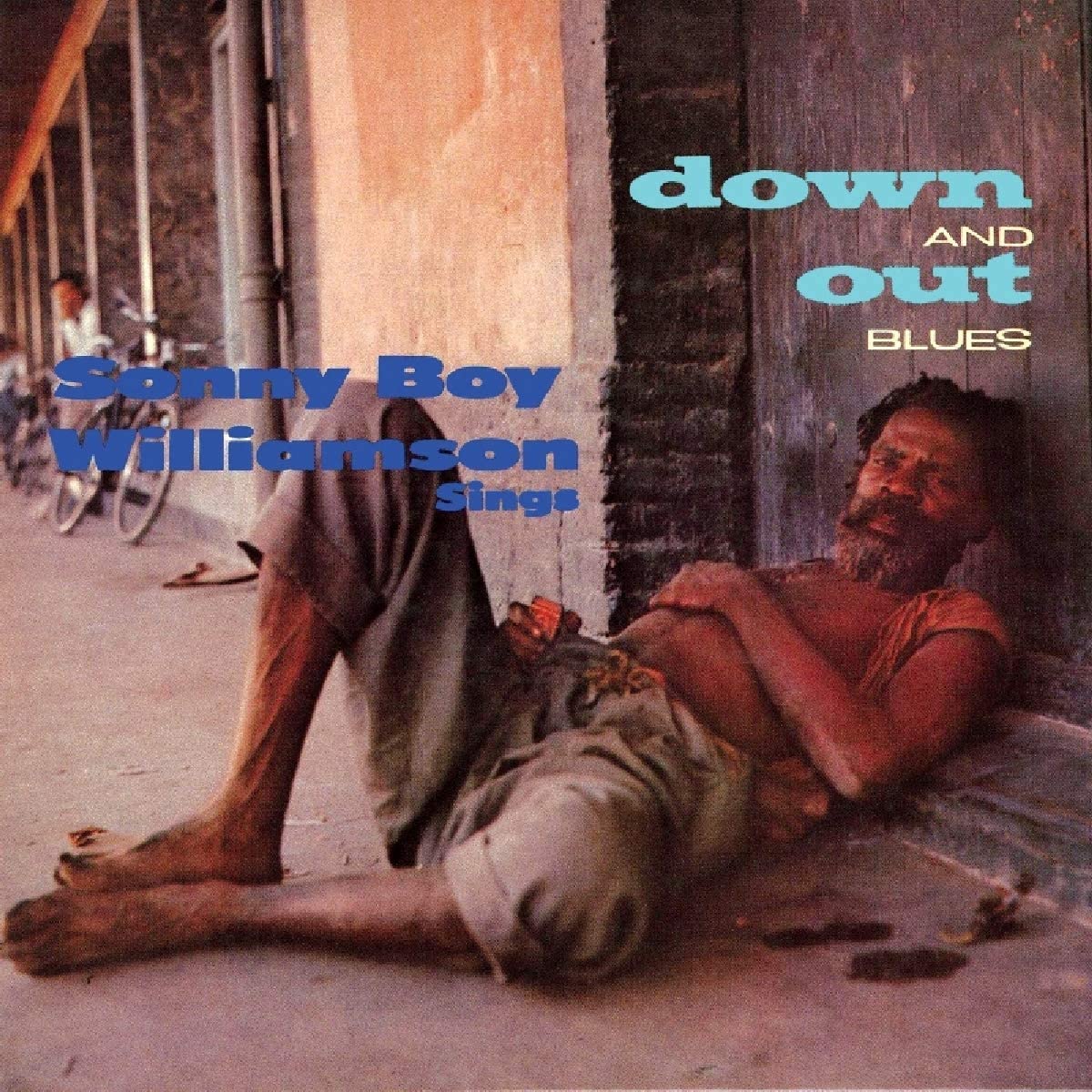

And so, to those two performances from Manchester and Copenhagen, which were played to me by an ‘in the know collector’ in London when I was 19 nearly 23 years ago! One is a video of his performance of a song called Keep It To Yourself on Granada Blues special from Manchester (see above) and the second is a recording of The Sky Is Crying from an album that was recorded in a marathon session in Copenhagen (see below) – the best version and choice of the many tracks released and sequenced on Alligator records in the early nineties.

Both have spoken introductions by Sonny Boy and with both performances it’s that moment when the harmonica hits with all the qualities that I’ve described above that knocked me out and made me shiver. I later found out that Robert Plant, the Lead singer of Led Zeppelin, testifies to having shivered when he first saw Sonny Boy live and in person and have since read many comments from amazed YouTube viewers around the world confirming similar reactions.

If you type in ‘blues harmonica’ to YouTube it’s fitting and quite incredible that some 69 years after the recording of this performance that with over twelve million views it’s the most watched blues harmonica video on YouTube.

They say the art of blues is not WHAT you play it’s HOW you play it. Sonny Boy’s artistry is a testament to this and as such makes him the very best of his art form.

Join us in the next part of our ‘Deep listening’ series, when we will be focusing on Jimi Hendrix at Monterey – Rock me baby.